Venom-producing snake organoids developed in the lab

The dark and bright side of snakes and their venom have fascinated mankind for millennia. Snakebite kills more than 100.000 people (and disables an estimated 400,000 individuals) every year, while many more suffer from ophidiophobia, an abnormal fear of snakes.

The dark and bright side of snakes and their venom have fascinated mankind for millennia. Snakebite kills more than 100.000 people (and disables an estimated 400,000 individuals) every year, while many more suffer from ophidiophobia, an abnormal fear of snakes. However, their toxins are also a rich source for new medicines and were already used for treatments in ancient Greece. Since then, many drugs have been inspired by snake venom, including drugs that lower blood pressure lowering drugs and prevent bleeding. Still, even in modern medicine, it has been challenging to fully exploit snake venom for drug development purposes and to protect people against its lethal potential. A few main obstacles are the cumbersome and dangerous process of milking snakes and the difficulty of studying and modifying venom factors in the glands of the snake.

Three PhD students working in the group of Hans Clevers at the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht, the Netherlands, were inspired by their colleagues’ successes of growing mini-versions of mammalian organs in the lab, called organoids. They wondered whether this would work for reptilians too, and whether they might be able to produce venom in the lab. They set up a collaboration with snake experts in Leiden, Liverpool and Amsterdam to collect venom glands from 9 different snakes and attempted to grow miniature versions of these glands in a dish.

After some tweaking of the conditions used to grow human organoids, the researchers developed a recipe that supports the growth of snake venom glands indefinitely. “The similarity between the growth conditions for human and snake tissues was staggering, with the main difference being the temperature”, says Jens Puschhof (Hubrecht Institute). Since the body temperature of snakes is lower than that of humans, the venom gland organoids only grew at lower temperatures; 32ºC instead of 37ºC.

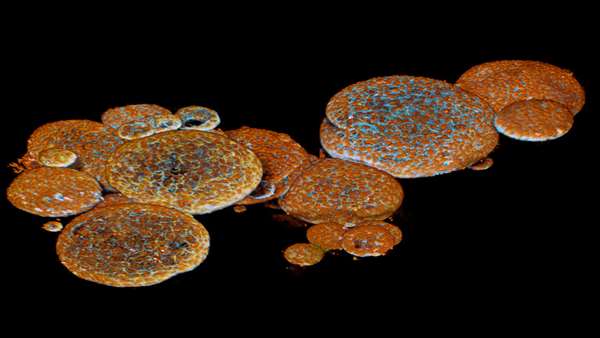

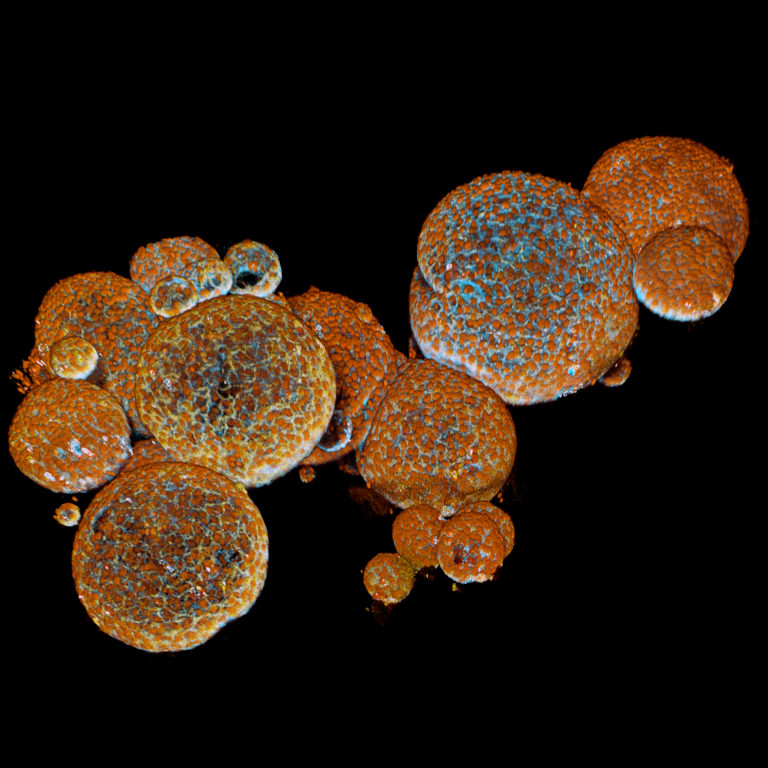

Through a high-resolution microscope, the researchers observed that the cells of the organoids are filled with dense structures that resemble the venom containing vesicles of the venom glands. Indeed, various analyses showed that the organoids produce the vast majority of venom components, or toxins, made by the snakes. For the first time, the researchers were able to study the toxin production of the individual cells in the venom gland. “We know from other secretory systems such as the pancreas and intestine that specialized cell types make subsets of hormones. Now we saw for the first time that this is also the case for the toxins produced by snake venom gland cells”, explains Joep Beumer (Hubrecht Institute). In addition, the researchers found that changing the factors in the growth medium of the organoids could change the composition of the venom, giving them control over the kind of venom that is produced. In a collaborative effort, they showed that neurotoxins produced by the organoids are active and can block nerve firing in various cell systems, similar to the neurotoxins produced by the snakes themselves.

Anti-venoms and drugs

The findings of the researchers may have far-reaching consequences. Venom produced by the snake venom organoids could be used for antivenom production as well as for targeted development of new venom-based drugs. Further studies are in progress to develop these applications in the future. In addition, growing reptilian organoids for the first time suggests that tissues from other vertebrate animals (such as lizards, or fish) could also be grown this way. In fact, the researchers are currently setting up a large collection of venom gland organoids from 50 toxic reptilians, snakes and other venomous animals together with reptilian expert Freek Vonk at Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands, to study these different kinds of venom in the lab. Yorick Post (Hubrecht Institute): “It was amazing to see that what started with our curiosity about potential snake venom gland organoids transformed into a technology with many potential applications affecting human healthcare”

Reference:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867419313236?dgcid=author

ارسال به دوستان