The iPS-cell field is hugely popular in Japan, in large part because it was a local scientist, Shinya Yamanaka at Kyoto University, who discovered how to make the cells. Expectations for the potential uses of iPS cells soared in 2012, when Yamanaka won the medicine Nobel prize for his 2006 discovery. In 2013, the Japanese government announced that it would pour ¥110 billion over the next ten years into regenerative medicine.

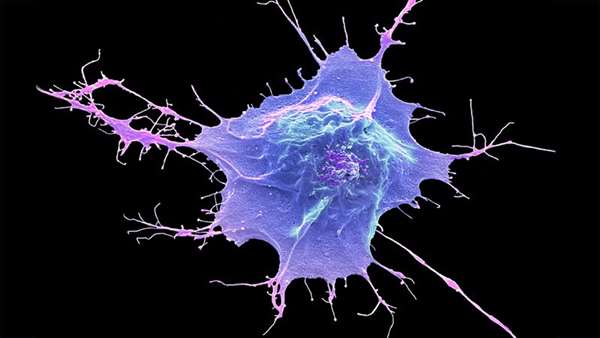

The country has invested hundreds of millions of dollars into research on induced pluripotent stem cells to treat diseased organs. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are those that have been reprogrammed from mature cells — often taken from the skin — into an embryonic-like state. From there, they can then turn into any cell type and be used to repair damaged organs.

Some of the first trials to test whether reprogrammed stem cells can repair diseased organs have begun to report positive results. But many researchers are cautious about overstating the significance of the trials, saying they were small and the results have yet to be peer reviewed.

In January, researchers reported that the first person in Japan given a transplant of heart-muscle cells made from reprogrammed stem cells had experienced improved heart function following the procedure. Then in April, another group announced that several people's vision had improved after transplanting corneal cells made from reprogrammed stem cells - a world first. The cornea study was designed to treat people who have severe visual impairments because they lack the stem cells needed to repair the cornea.

Starting in 2019, ophthalmologist Kohji Nishida at Osaka University in Japan used donor-derived iPS cells to create sheets of corneal cells, which were implanted into one eye in each of four participants. Nishida’s trial is not the first to use iPS cells to repair eye disorders.

In 2014, Takahashi led two studies using iPS cells to treat seven people with macular degeneration a condition in which eyesight deteriorates progressively. In those studies, the participants’ vision did not get worse. scientists say it is difficult to show whether the cells contributed to slowing vision deterioration.

There are also promising signs from another ongoing trial, in which donor cells are reprogrammed into heart-muscle cells, says trial leader Yoshiki Sawa, a cardiac surgeon at Osaka University. Sawa now says that all three — aged in their fifties, sixties, and seventies — have recovered and are working.

It is not clear whether any observed improvements in symptoms were a direct result of the transplanted cells or due to other aspects of the surgery.

Takahashi, a neurosurgeon at Kyoto University is involved in one trial expected to report results soon, in which researchers used donor-derived iPS cells to generate neurons that produce dopamine. They implanted these into the brains of seven people with Parkinson’s disease between 2018 and 2021. Takahashi says that no severe adverse events have been observed so far. Participants are being observed for two years after surgery, and their neurological symptoms will be assessed, with results expected in 2024. “The best scenario is that the patients’ symptoms get better,” he says.

The government’s 2013 investment in the field is due to end next year, and the cornea result in particular might help to justify continued investment in the technology.

To get industry support, scientists need to show that the therapies work. Results from ongoing clinical trials will be crucial.

Pioneering stem-cell trials in Japan report promising early results (nature.com)

ارسال به دوستان