European researchers announced recently that a new treatment for advanced melanoma was more effective than the leading existing therapy in a Phase 3 clinical trial.

The treatment, which uses a patient’s own immune cells to fight the cancer, has some similarities to another type of treatment that has proven to be highly effective for blood cancers, called CAR-T therapy.

CAR-T therapy involves harvesting a patient’s T cells and modifying them in the lab to turn them into cancer fighters, then infusing the cells back into the patient. The personalized treatment was first shown to be successful a decade ago in certain leukemia patients; it’s now also used for lymphomas as well as multiple myeloma.

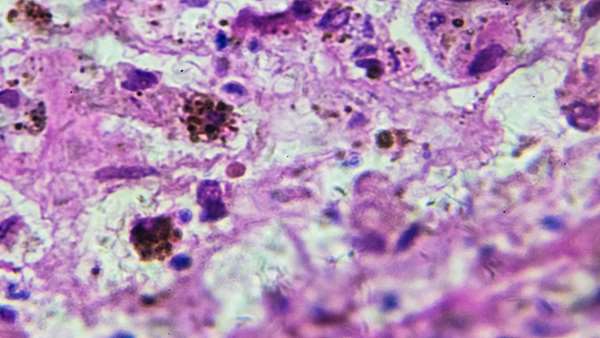

And while it’s been explored for solid tumors, which make up the majority of cancers, including melanoma, these tumors present challenges that blood cancers do not. Many blood cancers are homogeneous, meaning their cells are uniform. This gives CAR-T therapy a clear target to latch onto and attack. But solid tumors tend to have a number of different cell types that vary largely between cancer types, said Dr. Vincent Lam, an assistant professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, who specializes in immunotherapies.

This heterogeneity of the tumor cells makes finding a convenient and universal CAR-T target difficult in solid tumors, said Lam, who was not involved with the new research.

In the melanoma trial, doctors used an approach called TIL therapy. It involves harvesting a patient’s immune cells — in this case, cells called tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which are taken from the tumor — but instead of modifying them in the lab as they would with CAR-T therapy, they’re simply amplified to produce billions of cells.

Those cells are then infused back into the patient’s bloodstream, where they can work to kill the cancer.

“We expand them from a million cells to several billion cells,” Dr. John Haanen, a medical oncologist at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, who led the new clinical trial, told NBC News.

In the trial, 168 patients with metastatic melanoma were randomly assigned to receive either TIL treatment or the current standard treatment, an immunotherapy drug called ipilimumab. Ipilimumab is typically used in people who don’t respond to a first-line treatment called anti-PD-1 therapy; nearly all of the patients in the trial had not responded to that treatment.

The patients were followed for a median of almost three years. Compared to those who were treated with ipilimumab, patients on TIL therapy had a 50% reduction in disease progression and death.

In the TIL therapy group, 20% saw their tumors disappear completely, compared to 7% in the ipilimumab group. The patients are still being tracked, but so far, the median overall time of survival for cancer patients who received TIL therapy was over two years, compared to just over 1.5 years for those receiving ipilimumab. If a patient is able to get into complete remission, the chances that it will last years are high, Haanen said.

“For a population that has already failed one treatment, this is very good news,” he said.

According to Dr. Michael Davies, chair of melanoma medical oncology at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TIL therapy has been used in clinical trials to treat melanoma for nearly two decades, but this was the first one to compare it to an approved drug head-to-head. The kicker is that it was found to be superior.

“It’s the first time that we’ve had a result like that with a cell therapy immunotherapy for patients with melanoma,” said Davies, who is on the scientific advisory board for Iovance Biotherapeutics, a California-based company that is conducting a Phase 2 trial on TIL therapy in melanoma patients who failed anti-PD-1 treatment.

By itself, the therapy causes very few side effects and none that are long-lasting, Haanen said. However, in order for it to be effective, TIL therapy must be used in conjunction with chemotherapy and another drug called interleukin-2, or IL-2, which both have wide-reaching side effects.

“When you introduce billions of cells, you cannot just add them to the body, you have to make space, and the chemotherapy does that by killing off cells,” Haanen said. Then, once the patient receives the infusion of their own, lab-grown cells, the IL-2 helps the new cells survive.

Dr. Steve Rosenberg, chief, Surgery Branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, cautioned that the results of the trial can only be applied to metastatic melanoma, but added that there is a growing body of research exploring TIL therapy for other solid cancers, including lung and cervical cancers.

TIL therapy is also still likely years away from being approved for use outside clinical trials, which would open it up too many more patients with metastatic melanoma. Multiple U.S.-based companies are also studying TIL therapy.

ارسال به دوستان