New Gene Treatment Effective for Some Leukemia Patients

A new way of genetically altering a patient’s cells to fight cancer has helped desperately ill people with leukemia when every other treatment had failed, researchers reported on Monday in the journal Nature Medicine.

A new way of genetically altering a patient’s cells to fight cancer has helped desperately ill people with leukemia when every other treatment had failed, researchers reported on Monday in the journal Nature Medicine.

The new approach, still experimental, could eventually be given by itself or, more likely, be used in combination treatments — analogous to antiviral “cocktails” for H.I.V. or multidrug regimens of chemotherapy for cancer — to increase the odds of shutting down the disease.

Researchers say the treatment may be more promising as part of a combination than when given alone because, although some patients in the small study have had long-lasting remissions, many others had relapses.

The research, conducted at the National Cancer Institute, is the latest advance in the fast-growing field of immunotherapy, which fires up the immune system to attack cancer. The new findings build on two similar treatments that were approved by the Food and Drug Administration this year: Kymriah, made by Novartis for leukemia; and Yescarta, by Kite Pharma for lymphoma.

In some cases, those two treatments have brought long and seemingly miraculous remissions to people who were expected to die.

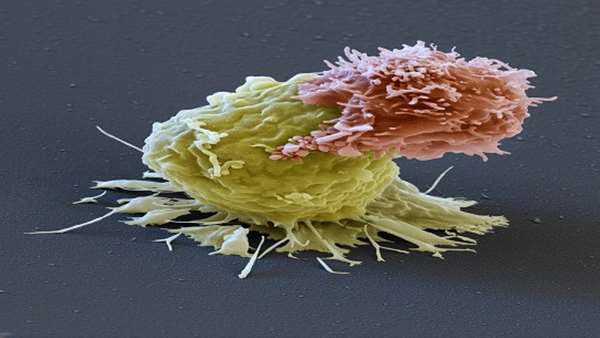

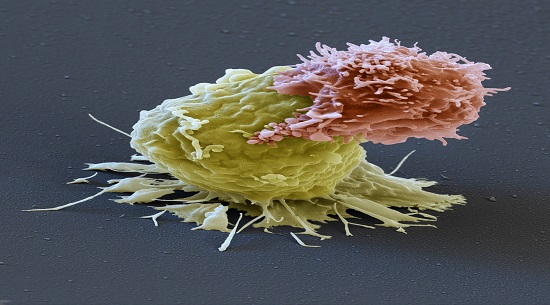

Kymriah and Yescarta require removing millions of each patient’s T-cells — disease-fighting white blood cells — and genetically engineering them to seek and destroy cancer cells. The T-cells are then dripped back into the patient, where they home in on protein molecules called CD19 found on malignant cells in most types of leukemia and lymphoma.

The new treatment differs in a major way: the T-cells are programmed to attack a different target on malignant cells, CD22.

Researchers have been eager to test this type of T-cell. One reason is that they hoped to find that CD19 was not the only vulnerable target, “not some kind of unicorn,” said Dr. Crystal L. Mackall, the senior author of the study and the associate director of the Stanford University School of Medicine’s cancer institute. Cancer cells are highly adaptable and often find ways to evade treatments aimed at only one target.

“The idea that we could have one magic bullet is naïve,” she said.

Another reason is that some patients with leukemia or lymphoma do not have CD19 on their cells, so the existing T-cell treatments do not work for them.

Other patients, perhaps 30 percent or more, have CD19 at first and go into remission when treated, but then lose the protein and relapse within six months — a wrenching outcome for patients and their families, whose hopes soar and then crash.

In theory, a treatment that goes after a different target could rescue patients who lack CD19 or lose it.

An even more important reason for the interest in a new type of engineered T-cell is that it would enable scientists to develop combination immunotherapy that would attack cancer cells on different fronts at the same time — a proven key to success with chemotherapy.

Dr. Mackall said a new T-cell treatment that attacks both targets at once is already being tested at Stanford. Last week, Seattle Children’s also opened a study of this combination treatment for children and young adults.

“The best way to go is to treat up front with a combination of 19 and 22,” said Dr. Carl H. June, a pioneer in T-cell treatments at the University of Pennsylvania, which he said would also be studying the treatment.

“That should make it ‘game over’ for the leukemia. I think that will paint it into a corner, and we’ll no longer see that kind of relapse. I’m really excited about it.”

The report in Nature Medicine is the first to describe a study of a treatment targeting CD22 in humans. The therapy was developed at the National Cancer Institute, and Dr. Mackall said researchers did not know if a company would try to bring it to market.

The subjects were 21 children and adults from 7 to 30 years old, with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia who had run out of options for treatment. Many had already been treated with T-cells directed at CD19 and had relapsed.

All had undergone at least one bone-marrow transplant, an arduous treatment with severe side effects.

Different doses of the T-cells were tested. At the lowest dose, one of six patients had a complete remission, meaning that all signs of leukemia went away.

But at a higher dose, 11 of the remaining 15 — 73 percent — had complete remissions, which lasted a median of six months. Three are still in remission, at six, nine and 21 months after being treated.

The results, the researchers say, are comparable to those achieved with T-cells directed at CD19.

The study is the first to show that patients who had previously been given CD19 treatment and relapsed could later be rescued by a different T-cell treatment, said Dr. Terry J. Fry, the first author of the study, from the National Cancer Institute.

“You have a potent salvage regimen,” he said.

The study may be able to treat 50 or 60 more patients, Dr. Fry said. Patients are on a waiting list to get in.

“They don’t have other options,” Dr. Fry said.

But though some have long remissions, for others the relapse rate is high. A sobering discovery, Dr. Mackall said, was that the cancer cells did not have to lose all their CD22 molecules, but only some, to escape the T-cells.

After relapses, a number of the patients died, Dr. Fry said.

“In pediatric oncology, a three-month remission, it’s great but it’s not where we want to be,” he said. “We want to cure patients. How do you improve on what’s already been demonstrated as an effective therapy?”

“The concept of cancer treatment is combining multiple types of therapies. This opens the door to try to use multiple targets to try to chip away at resistance.”

Reference: https://www.nature.com/articles/nm.4441

ارسال به دوستان