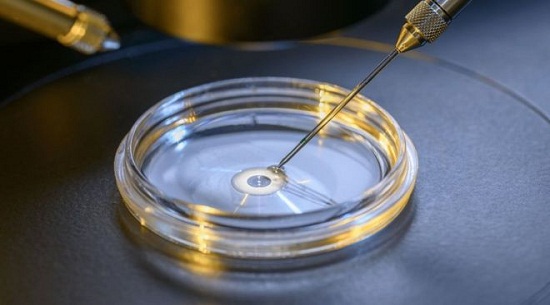

DNA surgery on embryos removes disease

The team at Sun Yat-sen University used a technique called base editing to correct a single error out of the three billion "letters" of our genetic code.

The team at Sun Yat-sen University used a technique called base editing to correct a single error out of the three billion "letters" of our genetic code.

They altered lab-made embryos to remove the disease beta-thalassemia. The embryos were not implanted.

The team says the approach may one day treat a range of inherited diseases.

Base editing alters the fundamental building blocks of DNA: the four bases adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine.

They are commonly known by their respective letters, A, C, G and T.

All the instructions for building and running the human body are encoded in combinations of those four bases.

The potentially life-threatening blood disorder beta-thalassemia is caused by a change to a single base in the genetic code - known as a point mutation.

The team in China edited it back.

They scanned DNA for the error then converted a G to an A, correcting the fault.

Junjiu Huang, one of the researchers, told the BBC News website: "We are the first to demonstrate the feasibility of curing genetic disease in human embryos by base editor system."

He said their study opens new avenues for treating patients and preventing babies being born with beta-thalassemia, "and even other inherited diseases".

The experiments were performed in tissues taken from a patient with the blood disorder and in human embryos made through cloning.

Base editing works on the DNA bases themselves to convert one into another.

Prof David Liu, who pioneered base editing at Harvard University, describes the approach as "chemical surgery".

He says the technique is more efficient and has fewer unwanted side-effects than Crispr.

He told the BBC: "About two-thirds of known human genetic variants associated with disease are point mutations.

"So base editing has the potential to directly correct, or reproduce for research purposes, many pathogenic [mutations]."

The research group at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou hit the headlines before when they were the first to use Crispr on human embryos.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, from the Francis Crick Institute in London, described parts of their latest study as "ingenious".

But he also questioned why they did not do more animal research before jumping to human embryos and said the rules on embryo research in other countries would have been "more exacting".

The study, published in Protein and Cell, is the latest example of the rapidly growing ability of scientists to manipulate human DNA.

It is provoking deep ethical and societal debate about what is and is not acceptable in efforts to prevent disease.

Prof Lovell-Badge said these approaches are unlikely to be used clinically anytime soon.

"There would need to be far more debate, covering the ethics, and how these approaches should be regulated.

"And in many countries, including China, there needs to be more robust mechanisms established for regulation, oversight, and long-term follow-up."

Reference: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13238-017-0475-6

ارسال به دوستان