Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy (CAR-T cell therapy) has revolutionized the treatment of blood cancers. CAR-T cell therapy has three main problems that Mayo is seeking to address to bring the full potential of this promising treatment to patients, says Saad Kenderian, M.B., Ch.B., a Mayo Clinic researcher.The first problem is toxicity. In amping up the immune system to fight cancer, the technique can unleash a torrent of pro-inflammatory cytokines known as a "cytokine storm" that can be toxic to the brain.

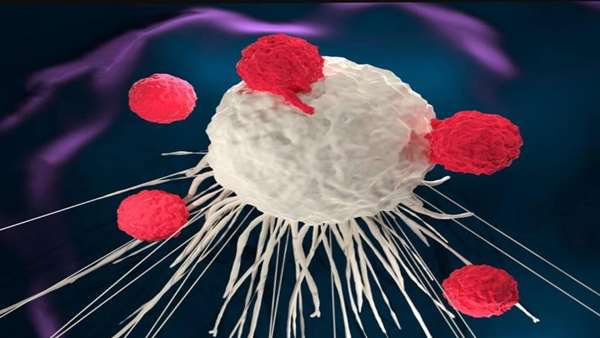

The second problem — and the focus of Dr. Kenderian's research — is that CAR-T cell therapy only achieves long-lasting results in a small subset of patients.For example, clinical trials have shown that a single infusion of CAR-T cell therapy targeted against a molecule known as BCMA that marks multiple myeloma cells prompted remission in 80%–100% of patients.But most of those patients relapsed within two years, as the CAR-T cells became dysfunctional," says Dr. Kenderian.He hypothesized that this dysfunction was caused by the tumor microenvironment. Kenderian's laboratory discovered that specific cells in the microenvironment — known as cancer-associated fibroblasts — exuded chemicals that kept the CAR-T cells from doing their jobs. Dr. Kenderian believed that if they could get rid of those cells, then the CAR-T cells could get back to fighting cancer.

Reona Sakemura, M.D., Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Kenderian's lab, designed a CAR-T cell therapy that went after these cancer-associated fibroblasts at the same time as it went after the multiple myeloma cells. The researchers showed that this dual-targeting strategy made the CAR-T cells more potent, preventing the development of resistance in a mouse model of multiple myeloma.Even if researchers can make CAR-T stronger and less toxic, a third problem remains: access. CAR-T is a very complex and expensive specialized treatment.

Previous clinical trials evaluated a CAR-T cell therapy that targeted a molecule called CD19 antigen, which sits on the surface of many hematological malignant tumors. This therapy resulted in overall response rates of up to 90% in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and 50%–80% in lymphoma. Despite these initial responses, up to 40% of patients experienced a relapse as their tumors shed the CD19 antigens, marking them for destruction.

To treat this "antigen escape," Dr. Qin and his team designed a CAR-T cell therapy that targets a second cancer marker known as BAFF-R. They found that the approach promoted durable remission in preclinical models.

ارسال به دوستان