Scientists create intestine-derived organoids as a model to study necrotizing enterocolitis

Researchers have created novel multicellular models as a way to study necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). The models, created with fetal and adult intestinal tissues, have already provided researchers with insights into fetal immune reactions to gut-colonizing bacteria.

Researchers have created novel multicellular models as a way to study necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). The models, created with fetal and adult intestinal tissues, have already provided researchers with insights into fetal immune reactions to gut-colonizing bacteria.

Researchers described how they developed these models, called organoids, in a recent article published online in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

NEC is a severe gastrointestinal disease with a 30% to 50% mortality rate in premature infants with very low to extremely low birthweight. Despite decades of research, progress toward understanding the pathogenesis of the disease has been slow.

“The lack of human models has hampered research into NEC,” explained co-senior author of the study Alessio Fasano, MD, director, Mucosal Immunology and Biology Research Center at MassGeneral Hospital for Children, and professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

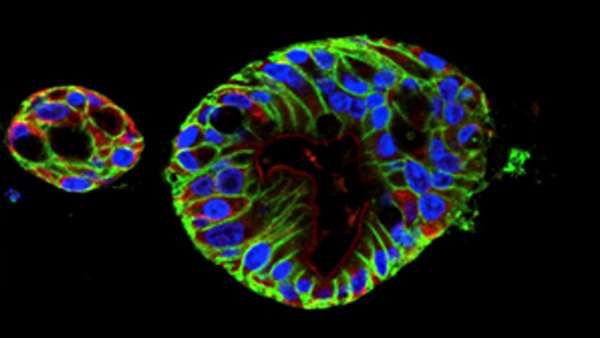

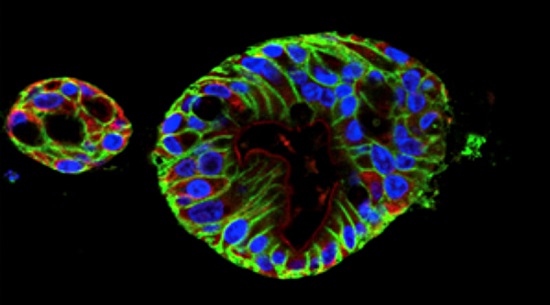

To develop a model, Dr. Fasano and colleagues used human intestinal samples to cultivate intestinal organoids at varying stages in fetal and adult development. The multicellular organoids, made of epithelial cells from the small intestine, allow researchers to study the fetal intestinal response related to the onset of NEC at different periods of development.

As an initial test, the investigators used RNA-sequencing to analyze gene expression of the adult and fetal organoids. The analysis showed that the fetal organoids clustered into two groups based on the developmental age of their respective tissue of origin: early (14 to 15 weeks) and late (17 to 22.5 weeks). The researchers predicted that the organoids in the later group would closely resemble the intestinal epithelium of a viable premature infant at higher risk of developing NEC.

“In the most premature infants, we think that the immature intestinal epithelial cells create an exaggerated immune response to commensal gut bacteria, contributing to the pathogenesis of NEC,” said the study’s first author Stefania Senger, PhD, geneticist and researcher in Dr. Fasano’s lab and instructor in Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School.

To investigate this immune response, Dr. Senger and colleagues exposed the early and late fetal organoids to commensal gut bacteria (Escherichia coli). The two groups of organoids had different reactions to the bacteria based on their developmental age—the late group demonstrated the exaggerated immune response, but the early group didn’t.

“This suggests that only fetal organoids from mature fetuses would be likely to react to bacteria as a premature infant would,” Dr. Senger said.

In other words, the late fetal organoids make a valid in vitro model to study NEC pathogenesis.

“The advantage of this approach is that we can build a repository of tissues from various stages of fetal and infant development,” said co-senior author Allan Walker, MD, Taff Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School. “Once you make an observation, you can go to the biorepository and use the organoid tissue to test that observation.”

Dr. Senger adds, “Not only does this promising new model of human intestinal organoids allow us to study this devastating disease, it also provides new tools to learn about infant gut development.”

Next, the researchers plan to culture organoids from infant intestinal tissue damaged by NEC to determine the mechanisms of inflammation that lead to the disease.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Reference: http://www.cmghjournal.org/article/S2352-345X(18)30021-3/fulltext

ارسال به دوستان