Pregnancy reported in the first known trial of ‘three-person IVF’ for infertility

A32-year-old Greek woman is reportedly pregnant from an experimental reproductive technique that uses DNA from three people — as part of the first known clinical trial to use the controversial procedure to treat infertility.

A32-year-old Greek woman is reportedly pregnant from an experimental reproductive technique that uses DNA from three people — as part of the first known clinical trial to use the controversial procedure to treat infertility.

The procedure, known as mitochondrial replacement therapy, is banned in the U.S., because of concerns that introduction of DNA from a third “parent” into an embryo is a form of genetic modification that could affect generations to come.

The first baby conceived with this technique was born in 2016, but in that case the purpose was to allow parents to have a child without passing on a genetic mutation that can cause a serious mitochondrial disease. A clinic in Ukraine has claimed additional births, but it is not part of a formal trial. If the method works better than conventional in vitro fertilization to treat infertility, it could lead to a radical new way to have children for older women and those struggling to get pregnant.

In 2015, the U.K. became the first country to formally approve the technique, but only in rare cases in which a couple is at high risk of having a baby with a serious mitochondrial disease. Now, Greece appears to be the second country to move ahead with the procedure.

For women with mitochondrial diseases, a step closer to preventing transmission

A Spanish company called Embryotools announced the pregnancy last week. The company is collaborating with fertility specialists at a clinic in Athens called the Institute of Life. The study is enrolling 25 women under 40 years old who have had at least two previous failed IVF attempts, according to a clinical trial listing. The team had to conduct the trial in Greece because the procedure is not approved in Spain.

Many countries’ laws aren’t clear about whether mitochondrial replacement therapy is illegal, which is why embryologists are taking an abundance of caution with where they carry out this procedure. In December 2015, the U.S. Congress prohibited the FDA from considering clinical trials in which a human embryo is intentionally created or modified, effectively banning mitochondrial replacement therapy.

Nuno Costa-Borges, scientific director and co-founder of Embryotools, said the team sought approval from the Greek National Authority of Assisted Reproduction, the government body that regulates fertility technology in Greece. The agency approved the trial at the end of 2016 but the team didn’t begin recruiting patients until last year.

“For some patients, it’s very hard to accept that they cannot get pregnant with their own [eggs],” Costa-Borges said in an interview. While donated eggs can significantly improve the chances of successful IVF in these patients, the resulting children are not genetically related to the intended mothers.

“Spindle transfer may represent a new era in the IVF field, as it could give these patients chances of having a child genetically related to them,” he said.

The pregnant woman in the trial had previously undergone two operations for endometriosis and four cycles of IVF without getting pregnant.

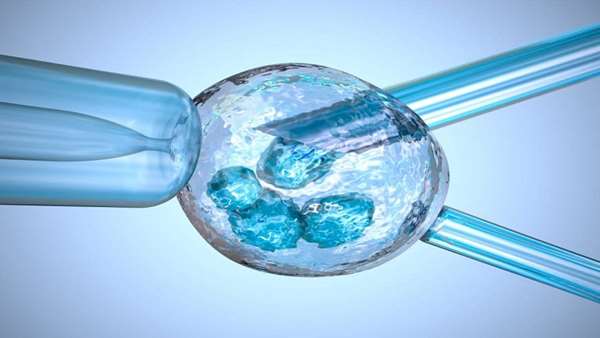

The Spanish and Greek team used a mitochondrial replacement technique called maternal spindle transfer, in which the nucleus — where most of the genetic material is located — is extracted from the intended mother’s egg and transferred into a donor egg, which has had its nucleus removed. The donor egg retains its healthy mitochondria, the energy suppliers of the cell, which float around in the watery fluid outside the nucleus. After that, the rest of the IVF process is the same: the modified embryo is fertilized with sperm and the resulting embryo is transferred to the uterus.

The procedure is often referred to as a “three-parent baby” technique or “three-person IVF” because, technically, the baby ends up with DNA from three people — the father, the mother, and an egg donor.

Poor egg quality is one of the reasons why IVF fails, and researchers like Costa-Borges think faulty mitochondria are a main culprit in many of these cases. So they reason that swapping the contents of an egg into another one with healthy mitochondria will solve this problem. For the same reason, rejuvenating an egg with healthy donor mitochondria might also eliminate the possibility of passing on disease-causing mitochondrial mutations.

“It is reasonable to hypothesize that mitochondrial replacement therapy may be beneficial for age-related infertility,” said Dr. Paula Amato, a OB-GYN at Oregon Health and Science University, where mitochondrial replacement therapy was pioneered by Shoukhrat Mitalipov.

First he pioneered a new way of making life. Now he wants to try it in people

Patients in the trial will not be randomized to mitochondrial replacement therapy or conventional IVF to compare live birth rates, which Amato said would be ideal. But there is a control group, according to Costa-Borges.

U.S. fertility doctor John Zhang used the same technique as the Greek and Spanish team to help a Jordanian couple get pregnant while avoiding passing on a fatal mitochondrial disease. Because the technique is banned in the U.S., Zhang went to Mexico to transfer the embryo into the mother. A seemingly healthy baby boy was born in 2016. It was the first successful attempt at mitochondrial replacement therapy (though babies had previously been born from an earlier technique using DNA from three people).

Zhang started a company called Darwin Life to commercialize mitochondrial replacement therapy for infertility in older women. But the Food and Drug Administration sent a strongly worded warning to Zhang saying he couldn’t advertise the procedure.

I. Glenn Cohen, a Harvard health law professor, said this new trial, as well as Zhang’s travel to Mexico for mitochondrial replacement therapy, may put pressure on the U.S. and other countries to change their policies for mitochondrial replacement therapy, noting these cases open the door to medical tourism.

“There is simply no way for any country to truly insulate itself from alterations through mitochondrial replacement therapy entering a country’s gene pool,” Cohen said.

Children will need to be followed into adulthood to make sure the technique doesn’t have any side effects, but Amato said the limited data so far suggest that the procedure is feasible and safe in humans.

“We are hopeful that continued success abroad will lead Congress to reconsider its ban on mitochondrial replacement therapy trials in the U.S. so that Americans can have access to this promising technology,” she said.

Reference:https://www.statnews.com/2019/01/24/first-trial-of-three-person-ivf-for-infertility/

ارسال به دوستان