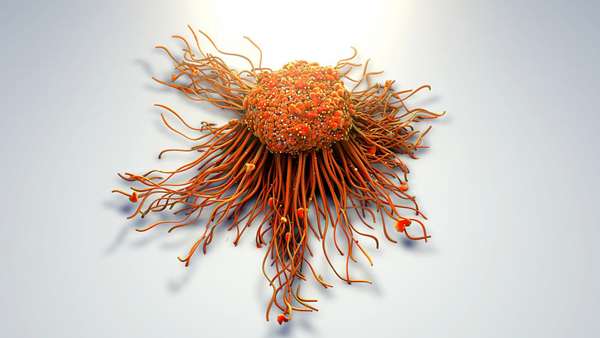

Cancer cells are quick-change artists adapting to their environment

Until now, researchers have assumed that the growth of solid tumors originates from cancer stem cells characterized by specific surface markers, which develop in a fixed, hierarchical order. Accordingly, such cancer stem cells are responsible for tumor progression and produce specific types of more differentiated cancer cells whose fates are predetermined.

Until now, researchers have assumed that the growth of solid tumors originates from cancer stem cells characterized by specific surface markers, which develop in a fixed, hierarchical order. Accordingly, such cancer stem cells are responsible for tumor progression and produce specific types of more differentiated cancer cells whose fates are predetermined. In a joint interdisciplinary project led by the Luxembourg Institute of Health (LIH), researchers now show that cancer cells of glioblastomas—conspicuously aggressive solid brain tumors—manifest developmental plasticity and their phenotypic characteristics are less constrained than believed. Cancer stem cells, including their progeny, are able to adapt to environmental conditions and undergo reversible transformations into various cell types, thereby altering their surface structures. The results imply that novel therapeutic approaches, which target specific surface structures of cancer stem cells, will be of limited utility. The research team has published its findings in Nature Communications in April 2019.

Glioblastomas are the most common malignant brain tumors. Because of their rapid growth, the prognosis for those affected is usually dismal. Many patients hold out hopes for novel therapeutic approaches, which utilize drug-bound antibodies directed against specific markers present on the surface of a subpopulation of immature glioblastoma cells. These antibody-drug conjugates bind to the surface, are then internalized and kill the cancer stem cells.

Remarkable cell state transitions

However, results now published in the journal Nature Communications suggest that this approach may be misdirected: "We exposed cancer cells in the laboratory to certain stressors, such as drug treatment or oxygen deficiency," explains Dr. Anna Golebiewska, Junior Principal Investigator at the NORLUX Neuro-Oncology Laboratory in LIH"s Department of Oncology and co-first author of the study. "We were able to show that glioblastoma cells react flexibly to such stress factors and simply transform themselves at any time into cell types with a different set of surface markers." This plasticity allows the cells to adapt to their microenvironment and reach a favorable environment-specific heterogeneity that enables them to sustain and grow, and mostly likely to escape also therapeutic attacks.

The team of scientists from Luxembourg, Norway and Germany, led by Prof. Simone P. Niclou at LIH, proposes that neoplastic cells of other tumor types may be also less constrained by defined hierarchical principles, but rather can adapt their characteristics to the prevailing environmental conditions. "The same phenomenon has been observed in breast and skin cancer," says Dr. Golebiewska. "This observation predicts that cancer therapies specifically directed against cancer stem cell markers may not be successful in patients."

The new findings could help to optimize future standard treatments. In laboratory experiments, the researchers were able to show that environmental factors, such as lack of oxygen in combination with signals from the tumor microenvironment, can induce cancer cells to modify their characteristics. This microenvironment, the immediate surroundings of the cancer, comprises cells and molecules that influence the growth of the tumor. "Once we understand exactly what causes the plasticity of tumor cells, we can devise combination therapies which target the signals underlying plasticity and thereby improve the therapeutic impact," underlines Dr. Golebiewska.

Collaboration and funding

The study is a collaborative work between the NORLUX Neuro-Oncology Laboratory and other research units and platforms at LIH. The researchers from LIH also worked in close collaboration with their long-term national partners to whom they are tightly connected through transversal research programmes: the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine at the University of Luxembourg and the Department of Neurosurgery of the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg. Moreover, the project was carried out with international partners from the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany, the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and the University of Bergen, Norway. This joint undertaking of different research and clinical players gives a truly interdisciplinary dimension to the study.

Reference:https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09853-z

ارسال به دوستان